Archaeology

Abernethy as a Pictish capital

Abernethy Round Tower

There are only two of the round high towers in Scotland that are often associated with the early monasteries in Ireland, and one of them is in Abernethy — a place that was an important Celtic Christian centre long before the influence of Rome saw St. Andrews established as Scotland’s main Christian centre. The other tower is at Brechin, another Christian centre highly important in the time of the Picts. Standing over twenty metres tall these towers have no openings in the walls apart from the elevated door, leading many to believe that they were primarily used for defensive purposes. One suggestion has been that the monks would take refuge in these towers whenever raiders approached, and marauding Norsemen are known to have been frequent visitors to our shores in the latter years of the first millennium.

Pictish stones

Who were the Picts? The Picts were the people of the north east of Britain during the first millennium AD. Their territory stretched from Shetland and Orkney in the north to the Forth and Clyde in the south, although at one time they may have also conquered and held land in Lothian. The name ‘Picts’ was first used of these people by the Roman historian Eumenius in 297AD, and appears to have referred to an amalgamation of several previously recorded Iron Age tribes. The Picts remained a powerful force for some centuries after this, but began to disappear from history in the ninth century as their society merged with that of the Scots from the west, and their distinct culture all but died out. With the exception of a list of kings and several untranslated Ogham stones, no Pictish writings are known to have survived, and this has meant that little is known for certain of their culture. Archaeology, however, has shown that the Picts were a nation of warriors and artists, who hunted, farmed, and erected stone monuments decorated with symbols and depictions of people and animals.

Pictish Stones.

Probably the most obvious (and a unique) feature of Pictish culture visible today is the collection of carved stones which can be seen across their territory. The stones are decorated with distinctive designs unique to Pictland, known as Pictish symbols, as well as scenes of everyday life and biblical stories. Pictish stones can broadly be divided into three different classes:

- Class I stones are thought to be pre-Christian and feature simple groups of symbols, rather than more complicated scenes or panels of interlace. They show no Christian imagery, and therefore are likely to be earlier than

- Class II stones, although there may have been a period of overlap as Christianity progressed through the region. Class II stones combine symbols with crosses or other Christian symbols. Many also feature depictions of bible stories, or church, hunting and battle scenes. Class II stones are generally thought to be later than Class I.

- Class III stones feature Christian emblems but have no Pictish symbols. They can range from simple carved crosses, dating from the earliest phases of Christianity in Pictland, to highly elaborate pieces created in the ninth century or later.

Pictish Symbols.

Many symbols are recorded but there are about twenty that occur regularly. These include animals and birds which would have been well known to the Picts, such as salmon and eagles; other animals, such as the ‘Pictish beast’ which may have been mythical or based on real animals; everyday objects such as a mirror and comb or tools, or shapes that appear to be abstract to modern viewers (such as the crescent and V-rod or the double disc), but may have been more obviously representational to the Picts. Even where symbols can be identified their meaning is uncertain. As they appear in small groups the different combinations may have identified particular people or groups. Some people believe that the Picts also painted or drew these symbols on their skin (the name ‘Picti’ seems to have been a nickname given by the Romans, meaning ‘painted people’), and the decoration of the stones may be related to this. Symbols have also been found carved on cave walls or engraved on metalwork.

The Purpose of Stones

Most Pictish stones no longer stand in the place where they were originally erected, having been moved or re-used as building material over the centuries. Because of this loss of context it is often unclear what their original purpose was. Some appear to have been grave markers and have been found in conjunction with individual burials or Pictish cemeteries. Others may have been used to mark boundaries or indicate ownership of a certain piece of territory.

The Romans in Tayside

The Romans arrived in Tayside nearly 150 years after they had first invaded Britain under Julius Caesar in 55 BC. Although Caesar, in order to impress public opinion in Rome, claimed that he had entirely subjected Britain, no Roman leader ever achieved this. Most of the Roman attacks focused on the south until, in the 60s AD, the Flavian dynasty came to power and successfully campaigned into northern England and Wales.

The next obvious target for the Roman invaders was Scotland, and under the British governor, Gnaeus Julius Agricola, armies were sent north. Agricola’s campaigns were later recorded by his son-in-law, the noted Roman historian Cornelius Tacitus, meaning that modern historians have a written version of events that they can use alongside the archaeological record to work out where the Romans went. Agricola’s campaigns north, which lasted from 79 AD to 85AD, ended after the battle of Mons Graupius in 83AD. This battle was probably fought somewhere in Aberdeenshire, although its exact location has never been discovered.

On his way north, Agricola established a chain of camps, including a small one at Carpow, near Abernethy, which served as one of his supply bases. Carpow stood at the confluence of the rivers Tay and Earn, and could easily be reached by water as well as by land. (It later became a fortress with a capacity of 2,000 or more). A probable Agricolan marching camp also stood at Carey, in the west of Abernethy parish. After the battle, the Romans retreated from Scotland, and did not attack the north again for over fifty years. In 138 AD armies led by Antoninus were dispatched to build a new fortification or ‘wall’.

This wall was to push the Roman frontier further north than the wall built shortly before by Hadrian, which ran between the Solway Firth and the Tyne. The new wall stretched across Scotland at its narrowest point (from the Clyde in the west to the Forth in the east), but unlike Hadrian’s Wall, which was built of stone, in this case as a safety precaution turf walls or ramparts and ditches around each camp site were quickly established . Although the tents left little mark on the landscape for archaeologists today to see, the defences, as well as pits dug for latrines and rubbish, often survive as crop marks. Because the camps on each campaign were so often similar in style and size, and were spaced at regular distances, archaeologists have been able to link particular sites to particular campaigns and armies, even where no datable finds exist, and can sometimes calculate where camps which can no longer be seen would have been.

Monastery and churches

Brigid and Abernethy

The Parish Church at Abernethy is dedicated to St. Bride, who is more commonly known as St. Bridget or Brigid. The saint features in the two different legends associated with the foundation of the church of Abernethy. The first legend tells that during the late fifth century there were two rivals who wanted to rule the Pictish kingdom. One of the men seized the throne, and the other, Nechtan, son of Wirp, had to leave and go into exile in Ireland. While he was there, he met St. Brigid, who told him that his rival had died. He returned to Pictland and claimed his rightful position, and in thanks for the saint’s intervention he granted Abernethy to God and St. Brigid.

In the second foundation legend, set 100 years later in the late sixth century, the Pictish king Gartnait, son of Domnach, founded and built the church of Abernethy, and gave land to God, St. Mary and St. Brigid, after St. Patrick brought St. Brigid and her followers to Pictland. Although it is highly unlikely that either of these foundation legends can be taken as literal truth, there does seem to have been a link between Abernethy and St. Brigid from early times, possibly as the result of churchmen or women from Ireland coming to Scotland and bringing Brigid’s cult or relics with them.

Brigid’s Life

Although Brigid is probably the most famous Irish saint after Patrick, very little is known for certain about her life. Her story was written and rewritten throughout the Middle Ages, and the supposed facts often differed between accounts. The earliest Life of Brigid, by Cogitosus, was written only a century after her death, but the author was concerned more with describing her miracles than her life. Because so little is known for certain, some historians have suggested that she did not actually exist, but was instead a representative figure, made up of other holy women and Irish pagan characters. There is no real reason to doubt Brigid’s existence, but much of what has been attributed to her does come from traditional Irish folklore or other saints’ lives.

It is generally accepted that Brigid was born in Ireland around 450 AD, although several places have been claimed as her place of birth. One account says that her parents were slaves, but the more common version is that her father, Dubthach, was a chieftain and her mother, Brocseach, was either a Christian noblewoman or Dubthach’s slave! When she was a young girl, Brigid took the veil under the guidance of St. Mel, and it is said that he mistakenly consecrated her as a bishop. About the year 470 she founded a double monastery at Cill-Dara (Kildare) and was Abbess of the convent, the first in Ireland. The foundation developed into a centre of learning and spirituality, and the illuminated manuscripts produced there became famous, especially the Book of Kildare, which was believed to be one of the finest of all illuminated Irish manuscripts before it was lost three centuries ago. Brigid died at Kildare around 525 AD on 1st February, which became her Saint’s Day.

She was buried at Kildare, but a later tradition claims that her remains were moved to Downpatrick to protect them from Vikings, and that she is now buried with SS Patrick and Colmcille.

The Pagan Goddess

Brigid, meaning ‘exalted one’, was also the name of an Irish pagan goddess and many of the attributes with which the saint is credited were those which were particularly respected in pagan times, such as healing powers, great learning and the gift of poetry. Kildare, also means ‘the church of the oak’, suggesting that there had been a pagan sanctuary there before the church, and St. Brigid's Day (1st Feb.) is the same date as Imbolg, the pagan festival of spring. The saint is often associated with fire and the sun, which may be a remnant of a pagan cult. A perpetual flame was tended at Kildare by a group of nineteen nuns until after the Reformation, and the remains of the flamehouse can still be seen.

Stories about Brigid

One day while she was tending her sheep, there was a very heavy downpour of rain and the saint was soaked to the skin. When the sun came out again she was dazzled, and mistaking a sunbeam for the branch of a tree, hung her cloak on it until it dried out.

One day Brigid visited a dying chieftain. As she sat by his bedside praying, she picked up some rushes from the floor and began plaiting them into a cross. The man was curious about what she was doing, so she explained that the cross was a symbol of God’s love. As she told him about her religion, he became very impressed, and converted before he died. In some places, it is still the custom to make these crosses on St. Brigid’s Day to ensure good luck for the household over the coming year.

In 2022 a new exhibit was introduced to the Museum of Abernethy on the ‘Witches’. Many brought up in Abernethy had heard tell of how the witches helped build the tower, or how they were executed on Castle Law Hill, but research has revealed a very different story; not the 22 believed to be buried in the ‘Witches’ Graves’, but records of only three women and two men, accused under the Scottish Witchcraft Act of 1563. The exhibit examined the relationship of the Abernethy accused to the situation across Scotland and gave the women faces; local faces. Ones you might see walking down the street…

Witchcraft in Scotland and Abernethy

The Reformation was heralded in Perth in May 1559 by John Knox’s inflammatory sermon in St John’s Kirk. A violent uprising followed and people’s choices of worship and belief became the lens through which neighbours judged each other. The Witchcraft Act of 1563 was passed in the wake of the Reformation. An act of the second Protestant parliament, it was a move by the government to establish Protestantism by legal, as well as ecclesiastical, means. While religious fervour was a characteristic of all creeds in Scotland in this period, the witch hunt was primarily a Protestant crusade, and it became a platform for the reformed church to demonstrate its fight against the ‘superstition’ of the Catholic Church. The Kirk Sessions spent much of their time publicly punishing their congregation for fornication, adultery and the like, but witchcraft was the one ‘crime’ which crossed from ecclesiastical into secular law, the punishment being much more than public humiliation. One suspect as the original drafter of this act is Knox, and in his typical over-the-top style, some of the stronger language had to be altered before it could be ratified!

The earliest record of witchcraft known in the parish of Abernethy comes from an accusation in the Register of the Privy Council for 2nd of July 1601. It records the denouncement as rebels of two men, ‘Hew and Georg Methvenis’. They failed to appear before the council after being summoned on charges of theft, reset, witchcraft and sorcery. Their residence is given to be ‘Methven’s Coble’. This location had long been unidentified, but on Adair’s 1730 map, the area now known as Ferryfield of Carpow near Abernethy is annotated as ‘Methwin’s Coble’, suggesting this is the origin of these two men. Being in control of this important crossing of the Tay and Earn, they would have been in a position to take advantage of those using their services. A dispute may have gotten out of hand and the slanderous accusation of witchcraft was intended to lend weight to their other crimes. Whether or not they were ever brought to justice, their name appears to have survived them locally for at least 130 years after the accusation.

There is only one major period of witch-hunting in the county of Perth and this is in 1662, coinciding with the biggest peak across the whole of Scotland. 58 cases are currently recognised and it is from this period that the only other recorded cases are found for Abernethy. In the Privy Council minutes of January 1662.

“ Commission is ordained to be direct to Sir David Carmichaell, baylie of the regalitie of Abernethie, William Oliphant of Carpow, Jon Oliphant of Cairie, Archibald Douglas and Jon Balvard, Baylies of Abernethie, William Olophant of Provestmaines, Thomas McCaula there, or any fyve of them, for trying and judging of Elspeth Young, Jonet Crystie and Margaret Mathie, confessed witches in the parish of Abernethie”

There is no record of the fate of the three women, but as they are recorded as having confessed, there is little doubt that their treatment would have been the same as those in the nearby Crook of Devon; strangled by hanging, with their bodies burnt to ensure they were not reanimated by the devil.

The Scottish Witchcraft Act was repealed by central government in 1736, but the associated superstition did not rapidly depart from the psyche of the populace. A belief in witchcraft still lingered. Rowan trees, and their protective branches, survived in the cottage garden and fear of an accusation remained a real threat. A young boy from Carpow near Abernethy, John Brown, suffered accusations of witchcraft and consultation with the devil due to his untutored knowledge of Greek, Latin and Hebrew. The accusations were so pervasive that in 1745 he felt the need to write to the local moderator of the Kirk Session defending himself against the charges. His entry to a school of Divinity was objected to by one of the members on the grounds that his learning had come from the devil. The boy later became Rev. John Brown of Haddington, Professor of Divinity, and author of the self-interpreting Bible!

Life in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries was a tenuous balance. Health/sickness, feast/famine, subsistence/destitution. Medicine as we know it was not available and the charmers and healers were the people who could help stave off or cure disease. The accused, in some cases, were even protected by the community they lived in because they were the only resort for the sick or those trying to keep their children well. Even those seeking help faced the potential for torture, trial and ultimately execution. Daily survival, intertwined with hopes, fears and superstitions were very immediate to the survival of a community. Neighbours were interdependent, and community stability was crucial. Those who appeared to disrupt the balance were othered, those who scolded and argued with their neighbours, or who cursed and wished ill. Witchcraft was a convenient accusation to throw at them, to remove the problem and to have the status quo restored.

It is also difficult to ascertain if some of these witches ever even existed, or if they are the conglomerated folk memory of the horrible fate faced by those accused, tried and found guilty.

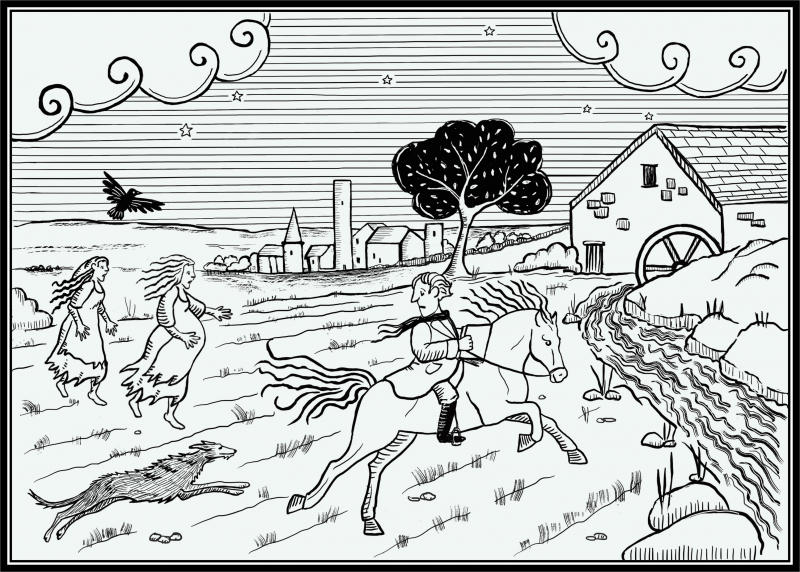

Abernethy is a good case in point. It boasts a witches’ walk, along which the convicted are alleged to have walked to their fate on the hill above the village, witches graves and a witches’ cave, the last of which is a shallow, obviously man-made cave hollowed from the basalt of the hill. One tale goes that the witches helped to build the round tower in the village, the construction of which is dated to around 1100AD. Some of these stories can be attributed to the work of Reverend Andrew Small, but others are an extention of his stories made up to explain things no-one quite understood.

As a result of the interest in the witch trials in Abernethy a grant application was made to Perth and Kinross Heritage Trust to obtain funding to erect a memorial to their lives. With funding obtained in 2022 we comissioned David McGovern of Monikie Rock Art to create a fitting peice of work. The memorial is now complete and plans for its installation and unveiling are afoot!

To quote Terry Pratchett “No one is finally dead until the ripples they cause in the world die away", our stone is creating new ripples for these women to live on in.